What is Palliative Care?

What is Palliative Care?

Hospice care has received much attention recently. This is in part due to increasing attention to end-of-life issues on the part of physicians and third-party payers. Substantially less attention has been paid to the category of “palliative care.” Hospice and palliative care are often conflated, but there are important differences between them. Understanding these differences can help individuals and their caregivers choose appropriate treatment options.

The differences between palliative and hospice care

According to the US National Library of Medicine, the ultimate goal of palliative care is relief of suffering in people with serious illnesses. One might argue that this should be the goal of all medicine, and indeed to some extent it is. However, palliative care is a much broader category that includes standard medical practice and extends beyond it. Palliative care is also directed at emotional, social and spiritual complications of serious

illness. The goal of this holistic approach is improved quality of life. It is important to stress that patients receiving palliative care may still be treated for various illnesses, from antibiotics for pneumonia to anti-cancer chemotherapeutic agents. The role of palliative care pharmacy services has become increasingly important in this regard.

Hospice care, by contrast, begins when curative treatment ends. The goals of hospice overlap substantially with those of palliative care, particularly in terms of pain and comfort measures. Hospice also seeks to maximize physical, emotional and spiritual comfort, though in a context outside of attempts to treat disease.

Where and when does palliative care take place?

Palliative care often begins in hospitals, although it can occur in long-term care facilities as well. Increasingly, individuals are receiving palliative care at home. The palliative care model has evolved such that it is very much a multi-disciplinary mode of treatment. Care teams consist of physicians, nurses and allied medical providers. Frequently various members of the same team continue to care for an individual through transition from an acute care facility to home.

Timing of care is another important distinction between hospice and palliative care. Hospice, by definition, only occurs when an individual is considered to suffer from a terminal disease or when the care team predicts, based on best evidence, that the individual is likely to live for 6 months or less. Palliative care, by contrast, begins at any time, and may continue through all stages of illness, whether or not the illness is terminal. Patients may receive palliative care at diagnosis, during follow-up and all the way through to the end of life. Many survivors of serious illness return to their treatment centers for decades after recovery.

Who pays for palliative care?

Because palliative care is often initiated in acute care settings, standard medical insurance usually covers the costs. For outpatient palliative care, prescription medications are often billed separately. These may or may not be covered by third-party insurers. Palliative care teams are generally aware of these restrictions and can help guide patients toward cost-effective treatment options. Many hospice programs, by contrast, are covered by Medicare, or commercial payers may cover services subject to policy limits.

The of pharmacies in palliative care

Because palliative care encompasses active treatment of medical conditions as well as comfort measures, pharmacy services are now integrated into palliative care teams in all care settings, from intensive care units to outpatient clinics. Now that a substantial amount of post-acute care services are delivered to patients’ homes, palliative care pharmacists are also developing expertise in preparation and delivery of medications for use both at home.

The current state of palliative care

The palliative care model appears to be relatively new, but in fact it is the oldest care model in medicine. Prior to the development of the modern pharmacopeia, there was not much a physician could do for a patient, apart from recommending diet changes, and perhaps various bathing regimens. Emotional and spiritual support was considered standard. With the development of scientific medicine in the 18th century, the holistic approach took a back seat to medical therapies. Therefore, we can think of the palliative care model as a return to medicine’s roots, where the patient comfort was paramount, and “do no harm” was the guiding principle.

Related Blog Posts

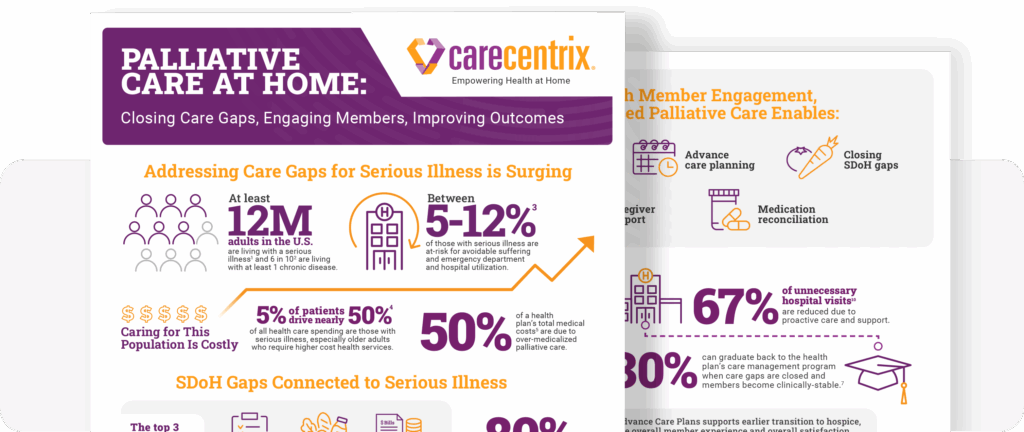

Palliative Care at Home: Closing Gaps, Engaging Members

Supporting members with serious illness can become costly. The need…

Family Caregivers: How Palliative Care Can Help

Facing a serious illness is overwhelming for patients, their family…

Moving Palliative Care from the Hospital to Home

Payors are constantly looking for ways to enhance the member…

Defining Vulnerable Populations in Healthcare

Defining Vulnerable Populations in Healthcare As providers, health plans, and…

4 Healthcare Trends that MA Plans Should Know in 2023

This year will be one marked by significant change and…

The Caregiving Crisis: How Health Plans Can Help

Over the course of my career caring for and developing…